Top 10 SF Films of the Decade (2000s)

Serenity – At first it might seem ridiculous and fanboyish to place Serenity higher than Children of Men. Not only is the latter more finely composed, but on first appearance Serenity appears not simply ramshackle but less stalwartly Science Fiction. While there are necessary paradigmatic environmental changes (the G-23 Paxilon Hydrochlorat, the psychic capacities of River Tam) they act less as central thematic drives than as crutches to drive events. If we take the old adage that a truly SF story is one that at its most basic and general can’t exist without a change of paradigm, it’s hard to evaluate Serenity because it’s hard to narrow down just what Serenity’s core is. Bad thing is done, man must expose? River finding family? Mal finding purpose? Blind faith? Totalitarianism? Tampering with natural order? There are so many disparate yet critical elements at work in Serenity and it moves so fast that one may be tempted to write it off as a desperate gasp than purely conceived and executed work. Yet I would argue that it is precisely Serenity’s linear, unraveling, scattershot density that marks it as a unique product of SF and a solitary masterpiece in the realm of film. Serenity reads like a Charlie Stross novel. Jumpy and uneven, railroaded from point A to B, dense with separately established half-ideas… and unbelievably all the better for it. That is to say an approach to narrative that could only exist and function well in the last couple decades of literary SF. And there’s no denying that Serenity functions well. Compressed seasons of Firefly or not, the film drips with the love it is clearly a labor of.

.

Children of Men – 2006 was a particularly good year for SF in the theaters and Children of Men was its crowning jewel. Everyone’s already seen this film, and I think that’s because it works so hard to encapsulate the everyday slowly decaying feeling of the Bush years. There is no scientific miracle or even new technology in Children of Men — consumer and industrial products are essentially the same, just with a different gloss, and a rainy, gritty, soggy wear and tear imposed over them. This is the future as the average person intuitively feels it. Exactly the same as today, just with the minor particulars evolved and the newspaper headlines darker. (To sustain this effect they had to remove the internet and infotech entirely.) Children of Men operates on the default assumptions you make when you first go to plot out your career or think about future generations. The world you directly touch will stay the same. And the rest of it will get worse, ultimately amounting to nothing. This is why Children of Men is without question the most accessible SF film of all time. It functions as a meditation on our relationship with SF and paradigmatic change more generally. The tediously building apocalypse beyond Britain, the paint-by-numbers insurgents within, the evolving fascistic state, all of these are operating within an antiquated context that has been dragged out for far too long. The absence of children is a vehicle for the exploration of the absence of ingenuity. Even though we assume they will and react negatively to claims that they won’t, in secret we don’t want things to stay the same. We want to be challenged by the new. The unseen. And its absence is the dissettling and unrealistic proposition.

.

A Scanner Darkly – The only Phillip K Dick film ever made. (It’s a shame because you’d assume they’d do well in Hollywood.) A Scanner Darkly is a loving tribute to paranoid deterioration. The tragedy isn’t that you don’t care anymore — you care all too much — it’s that you can’t clarify just what it is you care about. You can’t make sense of the world around you or even the particulars of your own life and your own identity because you’re lost in possibilities. A Scanner Darkly is not just a documentation of this state of mind, but an exploration of the unrealistic but not fantastical notion that maybe it was for something, maybe you had a plan all along. Maybe someone out there really does care for you. Maybe you are making a difference. That is to say “making a difference” in some higher form than offing yourself with a copy of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead and an unfinished letter to Exonmobile protesting the cancellation of your gas credit. Mundane sunny, suburban California never seemed so orwellian. And rotoscoped slipping and sliding cartoons of stoners arguing about the Beatles never seemed so dissettling. The delivery is an amazing triumph of everyday dystopia. But A Scanner Darkly’s core is a hauntingly utopian wish. That there was some unseen purpose, some triumph in failure. As the list of deceased scrolls by in PKD’s dedication, he plantatively asks if there might’ve been some happiness stolen in the midst of their abject misery. What would that even look like?

.

The Butterfly Effect – You know what I don’t give a shit. Ashton Kutcher made a good movie and you need to learn to accept that. The Butterfly Effect is the best time-travel film yet made, because it’s the most realistic, elegant and ressonant of them. That’s right, even with the ridiculous jumps forward it’s more on ball than Primer. None of this macroscopic bodily transference bullshit. The Butterfly Effect is the pure distilled essence of the time-travel story — cliche surrender in the face of complexity and inexorable self-sacrifice included. That it has no definitive ending is, kitchsy as it sounds, part of the appeal. Evan’s childhood is the whole point of the film, not whatever his ill-defined present might turn out to be.

.

Avatar – First, a bit on race: The rejected foreigner who is adopted by a tribe and fights his old tribe is an ancient and entirely valid plot concept. And there ARE plenty of Science Fiction or space fantasy stories told from the perspective of the colonized. It’s just that the subjects are always human (cf Independence Day, The Mount) because doing justice to the truly alien defies the bandwidth of storytelling. Avatar’s problem is that the Navi aren’t alien in the slightest — they’re deliberately made to be recognizable as our (simplistic, essentialist, idealic) impression of indigenous americans. This is both shallow and a bit fucked up. And it’s the reason Avatar tragically falls short of being a great film. It is, however, a very good film. Alas, there is no central component that marks it as inextricably SF. Like Serenity, Avatar is composed of a jumble of concepts, themes and struggles that work well together but defy simple summation. Nevertheless it’s worth pointing out just how positively many of them wax towards scientific inquiry and transhumanist self-expansion. Jake Sully is a broken, impoverished, outcast and marginalized man who desires nothing more than to excel — all his life he attempted this by following orders. But only by marrying his desire to self-improve with his twin brother’s desire to learn does he transcend both their failures and achieve the freedom and community he craves. But Grace Augustine is really what makes this film for me. How many decades has it been since we had scientists — much less scientific inquiry itself — portrayed in a positive light? I almost cried. Avatar has the most beautiful and realistic starship ever portrayed on the screen. It has imperialist soldiers being taken out by pteranodons. What the fuck more do you want?

.

A.I. – Kubric’s most surreal, ironic and pessimistic film ever required Steven Spielberg’s robotically emotional packaging to truly shine. I mean let’s be clear here. In the third act — in the frozen remains of an unsustainable civilization — it’s revealed that the act of consciousness trancends itself to become an undying legacy embedded in the cosmos. And the ressurected toy robot impulsively responds by irreversibly destroying his owner’s very soul so that he can experience a day’s fleeting intimacty with her once again. Saccharine my ass. A.I. is a twisted, glossy dystopic tale that sets out to excavate the uncanny valley on all fronts. The question “Are they people?” is always a false front for are we machines? And A.I.’s job is to vacillate as wildly as possible on this in as many ways as possible all while telling a coherent, emotionally gripping narrative. It has to get you to continue caring about the protagonists even as your perspective on that emotional atachment fluctuates. This is no small task. And it succeeds brilliantly. Naturally, the product is deeply dissettling. The well-worn dismissal that A.I. should have ended with the second act is, in fact, partially indicative of how successfully anticathartic the ostensibly cathartic third act is. A.I. has its faults — much of the social landscape in the second act simply fails to hit its target. But as a whole it is simply the best exploration yet of the classical Asimovian blur surrounding the animate objects we sympathize with.

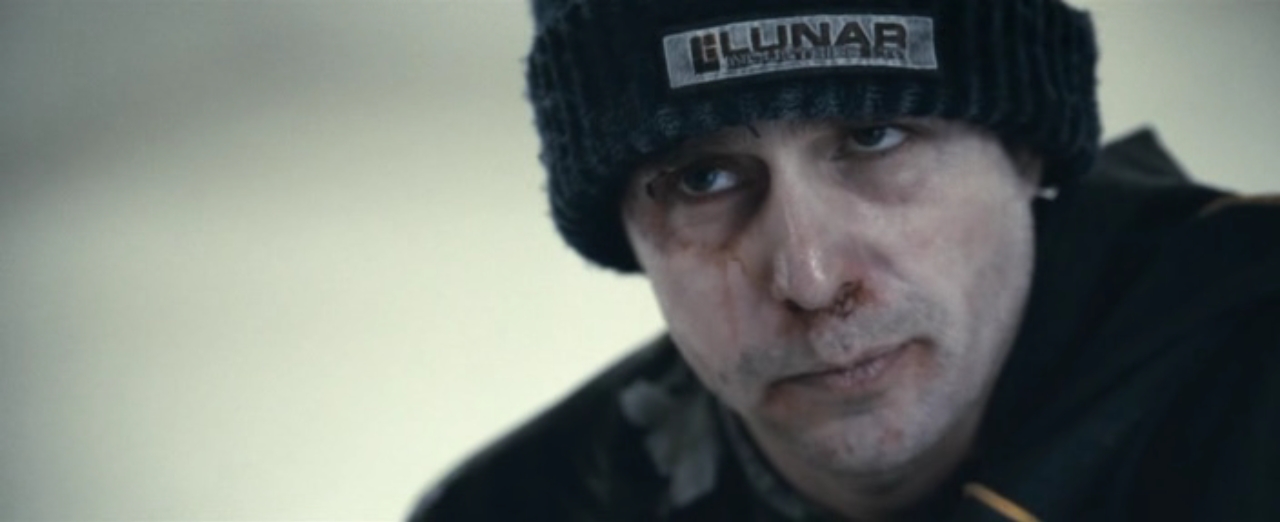

Moon – Sometimes an idea doesn’t need to be that fresh, or even profound. Sometimes the smallest of twists can shine simply by fleshing it out well. Moon is not going to surprise you. It’s going to walk you through the consequences so realistically that every scene will make that single thorny change stand out and impress you anew.

.

Primer – Primer has one trick: omission. It can make for a mildly challenging and sometimes even interesting puzzle, but cripples it as a dramatic. Primer is less Science Fiction than it is engineering fiction. An attempted study of time-travel mechanics (as opposed to coherent theory), it waxes into a study of the ever present paranoia and emasculation that is bourgeois geekdom. Of all the films to make this list Primer is the least in the vein of SF, and yet to omit it would be unconscionable. And not out of token appreciation of its twine-and-bubblegum-wrapper budget. Rather the film is this decade’s rare good example of that overly ballyhooed and only marginally SF tradition: exploring effects of a subtle alteration to examine the world as it is. Primer is most impressive as an accidental critique of capitalist culture. An alienated, shallow world where the effects of true ingenuity can only be stumbled upon and then furiously exploited for social power. Where control of a situation is possible, but almost entirely arbitrary. And ultimately naught but a veneer on the underlying self-destruction. Even framing the plot itself as a puzzle — a competitive test — helps create a meta environment similar to that of Abe and Aaron. So, whether always consciously intentional or not, Primer’s elements do add up to a neat trick and decent SF film. Would that we lived in a world where realistic dialogue and technical detail was anything other than an utterly unique breath of fresh air. Until then.

.

Sunshine – Oh, I know, it’s shit. But it’s a pile of shit that grows on you. Sunshine is Armageddon meets 2001. Without the upside of Bruce Willis but also without the sheer boredom of Clarke. It’s almost fatally crippled by its third act lapse into giving a damn about a paleolithic irrelevancy (the religious). And the director’s understanding of them scientists is lacking, to say the least. But somehow the film survives and arguably even flourishes. Yes, the material premise is borderline magical and only stated in its most cartoonish form on screen — strangelets be destroying teh sun — but if you knew anything about how little astrophysicists actually know about anything you’d be inclined to let it slide. But, the central premise of Sunshine is actually an aesthetic one: sunlight being more dangerous than darkness. It’s a hack of our visual neurological architecture. A mildly SF conceit that could only function on screen. Of course, one wishes the genre of pretty, immaculate spaceships with pretty, immaculate scientists had more entries to choose from. But Sunshine is at least the most watchable of them.

.

Pitch Black – Pitch Black is just a very satisfying film. That’s all there is to it. Characters are stranded and hunted by creatures. This vicerally delightful setup almost always works on the rare occasions it is truly embraced (Jurassic Park, Alien) because it negates post-modernism by directly tapping into simplistic material reason in a way that outright horror almost always fails. Horror films terrify by removing rules, by undercutting the security of our capacity to reason — either we stop being able to make sense of the world around us and default on animal instinct or we invest the entirety of our minds into understanding the twisted thinking of our enemy. In both cases there cease to be rigidly tangible rules, or at very least at times the utility of hard headed reason seems to be in question. Pitch Black, like the few adequately SF “being hunted by creatures” films before, generates fearful tension but never the intellectual abandon or psychological recursion of outright horror. The challenge faced is the natural world — an almost prototypical SF story. Granted some of the challenges are farfetched (the crazy orbital locking) and it’s a bit vexing to only see pretty much only one type of life in the biota, but the peculiarities are the payoff in Pitch Black. The film takes for granted that we’ve played this game before and simply tries to change up the character dynamics and setting enough to refresh the experience. In this it does extraordinarily well. It left all of us with enough goodwill to see Vin Diesel though his ridiculous spinoff trilogy, but really, all the characters are awesome.

.

Notably omitted titles: The Fountain is not really SF because the sf story is an in-film allegory. Similarly, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind came close but was so introverted and surreally subjective in subject and approach that it might as well be magical realism. Star Trek, while fun, is not SF because it’s fucking Star Trek.

Finally, District 9 hasn’t sat well with me since viewing. The inclusion and portrayal of the Nigerians smacks of direct racism, and the central premise is both too different to allegorize and too allegorized. It of course means to be unsettling but in the process I think it fails at being substantive.